My friend, who runs a plant phenology research lab at UBC, invited me out to Vancouver. About 12 years ago, I worked as a technician in her lab, back when it was in Massachusetts. The work was a fun mix of field work (read: long walks in the woods, across the Northeast), photography, and engineering. It was also memorable because everyone in our lab group was somehow simultaneously super nice and super talented. We all got along in a way I haven’t experienced in a professional environment since. The job was formative because it helped me realize I was more interested in making things than researching them.

So I went to UBC to give a talk and hang out with people in nearby biology labs who were building instrumentation for their experiments. It turns out research labs are often places where weird engineering happens. Scientists are trying to discover new knowledge, so they tend to need to build new things. Like centrifuges that spin mushrooms faster than ever. Or cameras you can mount to trees, or fish. Stuff like that.

Science turns out to be a good venue for mechanical and computational problem solving. Maybe especially because researchers, by nature of their scientific bent, bring the outside-the-box thinking and thriftiness that suits engineering. That these tools only need to work once, and don’t need to ship in volume, relieves constraints in a way that makes the making more fun and accessible. It’s a situation where your intuition is often enough to figure things out.

My friend put together a group of researchers for me to hang out with after the talk. I didn’t photograph everything since some of it was behind-the-curtain. Here’s at least a summary of what I came back with.

A current grad student in the lab, Charles, was deploying a small digital dendrometer in his greenhouse. A dendrometer measures tree diameter. This one was cleverly made of carbon fiber so it doesn’t expand and contract with temperature changes. If I recall, it also measures the magnetic field between two magnets, so it’s especially precise.

One of the lab’s former students, Dan, made an open-source camera robot for taking pictures of tree core samples. It was the thing at UBC that most closely resembled things I’d built. Dan is a trained engineer, and you could tell by the build quality. The main manifold of the gantry was purple, while the frame was black.

Unbeknownst to others in the room, a whole meditation on the color purple was happening for me internally. Purple has been an intriguing color to me lately. It’s like a masculine pink. Purple looks spooky but seductive when combined with black. Seeing black and purple together gives me a similar feeling as seeing Travis Barker and Kourtney Kardashian together.

Later on I met a guy who studies the mating patterns of a particular species of fish—not guppies, but something like them. He uses them as model organisms to study behavior in more complex animals, including humans. He has to keep track of thousands of fish in small tanks. His lab setup looked like that part of The Matrix where humans are incubated in pods and harvested for resources––but with fish.

Other scientists showed me instrumentation for studying plants underwater. They reminded me of hydroponic systems, where water flows in a loop.

We visited Dan’s new lab. It’s a half-a-football-field-sized simulated creek: ten-foot-wide, 100-foot-long channels filled with rocks, with water running through them. I’m trying to remember more details of the system, but the place was photogenic enough for me to sort of black out while he was talking. It was cool though.

After lunch, I went to an evolutionary biologist’s office and he immediately launched into our apparently shared interest in how to make microscopes for under ten cents. He’d noticed when I brought it up in my talk. “I’ve been making these little microscopes for 25 years,” he said. “Let’s go do a demo.”

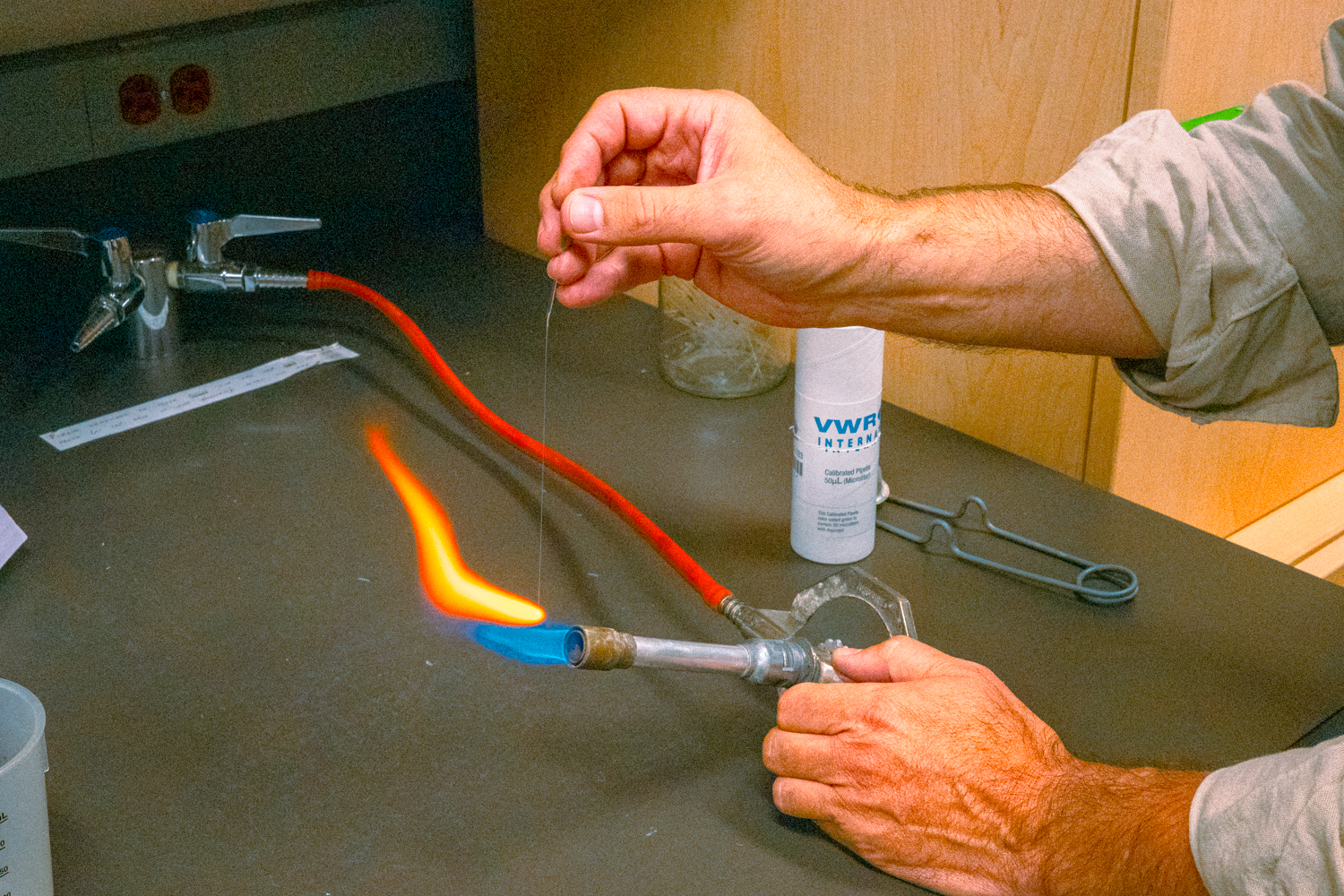

We went downstairs to his lab. He showed me how he makes the lens by heating a glass pipette over a flame. The heat causes a small globule of glass to form at the end. The globule becomes the microscope’s lens, at the end of the now tadpole-shaped fragment of the pipette. You mount the fragment into a piece of paper with a punch-out hole fitted for the spherical end. A ball of clay on the other end of the paper registers the object in focus with the press of the thumb. That’s the whole thing. It worked really well. I don't have any photos of looking through the microscope because I was excited and blacked out again.

I’d been experimenting with cheap microscopy in another context, so it was serendipitous to cross paths with a subject expert. If you squinted your eyes at us making it, you might have thought we were doing drugs.

At the end of the two days, the lab had a picnic at Jericho Beach Park. Everyone was cool. There were ketchup-flavored potato chips, which are apparently a thing in Canada. I wasn’t feeling them. :/

I went back to that high-concept retro-Chinese bar, Meo, for dinner afterward. Then turned in early and got ready to hike.

← back